The 2021 Dylan Thomas Prize Shortlist

The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so the longlist contained poetry collections as well as novels and short stories. Remaining on the shortlist are these six books (five novels and one short story collection; four of the works are debuts):

- Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat – Stories of the Syrian American experience.

- Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis – A novel about an elderly plane crash victim and the alcoholic park ranger who tries to find her. (See Annabel’s review.)

- The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi – A coming-of-age story set in Nigeria.

- Pew by Catherine Lacey – A mysterious fable about a stranger showing up in a Southern town in the week before an annual ritual.

- Luster by Raven Leilani – A young Black woman and would-be painter negotiates a confusing romantic landscape and looks for meaning beyond dead-end jobs.

- My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell – A nuanced look at the #MeToo phenomenon through the prism of one young woman’s relationship with her teacher.

It’s an American-dominated set this year, but, refreshingly, five of the six nominees are women or non-binary. I happen to have already read the last three of the novels on the list. I’m most keen to try Alligator and Other Stories and Kingdomtide and hope to still have a chance to read them. No review copies reached me in time, so today I’m giving an overview of the list.

This is never an easy prize to predict, but if I had to choose between the few that I’ve read, I would want Kate Elizabeth Russell to win for My Dark Vanessa.

(The remaining information in this post comes from the official Midas PR press release.)

The shortlist “was selected by a judging panel chaired by award-winning writer, publisher and co-director of the Jaipur Literature Festival Namita Gokhale, alongside founder and director of the Bradford Literature Festival Syima Aslam, poet Stephen Sexton, writer Joshua Ferris, and novelist and academic Francesca Rhydderch.

“This year’s winner will be revealed at a virtual ceremony on 13 May, the eve of International Dylan Thomas Day.”

Namita Gokhale, Chair of Judges, says: “We are thrilled to present this year’s extraordinary shortlist – it is truly a world-class writing showcase of the highest order from six exceptional young writers. I want to press each and every one of these bold, inventive and distinctive books into the hands of readers, and celebrate how they challenge preconceptions, ask new questions about how we define identity and our relationships, and how we live together in this world. Congratulations to these tremendously talented writers – they are master storytellers in every sense of the word.”

Francesca Rhydderch on Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat: “Dima Alzayat’s visceral, innovative Alligator & Other Stories marks the arrival of a major new talent. While the range of styles and stories is impressively broad, there is a unity of voice and tone here which must have been so very difficult to achieve, and a clear sense that all these disparate elements are part of an overriding, powerful examination of identity.”

Joshua Ferris on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis: “Kingdomtide is a propulsively readable and frequently very funny book about the resources, personal and natural, necessary to survive a patently absurd world. The winning voice of Texas-native Cloris Waldrip artfully takes us through her eighty-eight-day ordeal in the wilds of Montana as the inimitable drunk and park ranger Debra Lewis searches for her. This fine novel combines the perfect modern yarn with something transcendent, lyrical and wise.”

Namita Gokhale on The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi: “The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi is a powerful novel that carries the authenticity of cultural and emotional context. The story unfolds brilliantly, with the prescient foreboding about Vivek Oji’s death already announced in the brief line that constitutes the opening chapter. Yet the suspense is paced and carefully maintained until the truth is finally communicated in the final chapter. A triumph of narrative craft.”

Francesca Rhydderch on Pew by Catherine Lacey: “In this brilliant novel Catherine Lacey shows herself to be completely unafraid as a writer, willing to tackle the uglier aspects of a fictional small town in America, where a stranger’s refusal to speak breeds paranoia and unease. Beautifully written, sharply observed, and sophisticated in its simplicity, Pew is a book I’m already thinking of as a modern classic.”

Syima Aslam on Luster by Raven Leilani: “Sharp and incisive, Luster speaks a fearless truth that takes no hostages. Leilani is unflinchingly observant about the realities of being a young, black woman in America today and revelatory when it comes to exploring unconventional family life and 21st-century adultery, in this darkly comic and strangely touching debut.”

Stephen Sexton on My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell: “My Dark Vanessa is an articulate, uncompromising and compelling novel about abuse, its long trail of damage and its devastating iterations. In Vanessa, Russell introduces us to a character of immense complexity, whose rejection of victimhood—in favour of something more like love—is tragic and unforgettable. Timely, harrowing, of supreme emotional intelligence, My Dark Vanessa is the story of one girl; of many girls, and of the darknesses of Western literature.”

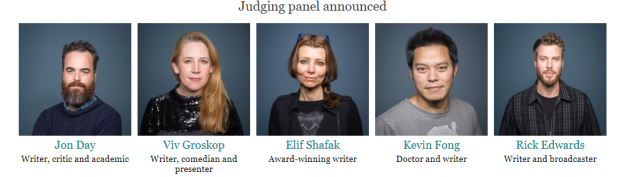

Wellcome Book Prize Blog Tour: Will Eaves’s Murmur

“This is the death of one viewpoint, and its rebirth, like land rising above the waves, or sea foam running off a crowded deck: the odd totality of persons each of whom says ‘me’.”

When I first tried reading Murmur, I enjoyed the first-person “Part One: Journal,” which was originally a stand-alone story (shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award 2017) but got stuck on “Part Two: Letters and Dreams” and ended up just giving the rest of the book a brief skim. I’m glad that the book’s shortlisting prompted me to return to it and give it proper consideration because, although it was a challenge to read, it was well worth it.

Eaves’s protagonist, Alec Pryor, sometimes just “the scientist,” is clearly a stand-in for Alan Turing, quotes from whom appear as epigraphs heading most chapters. Turing was a code-breaker and early researcher in artificial intelligence at around the time of the Second World War, but was arrested for homosexuality and subjected to chemical castration. Perhaps due to his distress at his fall from grace and the bodily changes that his ‘treatment’ entailed, he committed suicide at age 41 – although there are theories that it was an accident or an assassination. If you’ve read about the manner of his death, you’ll find eerie hints in Murmur.

Every other week, Alec meets with Dr Anthony Stallbrook, a psychoanalyst who encourages him to record his dreams and feelings. This gives rise to the book’s long central section. As is common in dreams, people and settings whirl in and out in unpredictable ways, so we get these kinds of flashes: sneaking out from the boathouse at night with his schoolboy friend, Chris Molyneux, who died young; anti-war protests at Cambridge; having sex with men; going to a fun fair; confrontations with his mother and brother; and so on. Alec and his interlocutors discuss the nature of time, logic, morality, and the threat of war.

There are repeated metaphors of mirrors, gold and machines, and the novel’s language is full of riddles and advanced vocabulary (volutes, manumitted, pseudopodium) that sometimes require as much deciphering as Turing’s codes. The point of view keeps switching, too, as in the quote I opened with: most of the time the “I” is Alec, but sometimes it’s another voice/self observing from the outside, as in Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater. There are also fragments of second- and third-person narration, as well as imagined letters to and from June Wilson, Alec’s former Bletchley Park colleague and fiancée. All of these modes of expression are ways of coming to terms with the past and present.

I am usually allergic to any book that could be described as “experimental,” but I found Murmur’s mosaic of narrative forms an effective and affecting way of reflecting its protagonist’s identity crisis. There were certainly moments where I wished this book came with footnotes, or at least an Author’s Note that would explain the basics of Turing’s situation. (Is Eaves assuming too much about readers’ prior knowledge?) For more background I recommend The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing.

I am usually allergic to any book that could be described as “experimental,” but I found Murmur’s mosaic of narrative forms an effective and affecting way of reflecting its protagonist’s identity crisis. There were certainly moments where I wished this book came with footnotes, or at least an Author’s Note that would explain the basics of Turing’s situation. (Is Eaves assuming too much about readers’ prior knowledge?) For more background I recommend The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing.

To my surprise, given my initial failure to engage with Murmur, it is now my favorite to win the Wellcome Book Prize. For one thing, it’s a perfect follow-on from last year’s winner, To Be a Machine. (“It is my fate to make machines that think,” Alec writes.) For another, it connects the main themes of this year’s long- and shortlists: mental health and sexuality. In particular, Alec’s fear that in developing breasts he’s becoming a sexual hybrid echoes the three books from the longlist that feature trans issues. Almost all of the longlisted books could be said to explore the mutability of identity to some extent, but Murmur is the very best articulation of that. A playful, intricate account of being in a compromised mind and body, it’s written in arresting prose. Going purely on literary merit, this is my winner by a mile.

My rating:

With thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

From Gallop: Selected Poems by Alison Brackenbury. Originally published in the volume After Beethoven.

Will Eaves is an associate professor in the Writing Programme at the University of Warwick and a former arts editor of the Times Literary Supplement. Murmur, his fourth novel, was also shortlisted for the 2018 Goldsmiths Prize and was the joint winner of the 2019 Republic of Consciousness Prize. He has also published poetry and a hybrid memoir.

Opinions on this book vary within our shadow panel; our final votes aren’t in yet, so it remains to be seen who we will announce as our winner on the 29th.

If you are within striking distance of London, please consider coming to the “5×15” shortlist event being held next Tuesday evening the 30th.

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the Wellcome Book Prize blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Wellcome Book Prize Longlist: Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning

“all these ideas are swirling around inside your head at once, hurling through your mind, it is on fire, so when you speak it all comes out muddled and confused and no one can understand you.”

Like the other Wellcome-longlisted title I’ve highlighted so far, Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi, Mind on Fire explores mental health. Its subtitle is “A Memoir of Madness and Recovery,” and Irish playwright Fanning focuses on the ten years or so in his twenties and thirties when he struggled to get on top of his bipolar disorder and was in and out of mental hospitals – and even homeless on the streets of London for a short time.

Fanning had suffered from periods of depression ever since his mother’s death from cancer when he was 20, but things got much worse when he was 28 and living in Dublin. It was the summer of 1997 and he’d quit a full-time job to write stories and film scripts. What with the wild swings in his moods and energy levels, though, he found it increasingly difficult to get along with his father, with whom he was living. He also got kicked out of an artists’ residency, and on the way home his car ran out of petrol – such that when he called the police for help, it was for a breakdown in more than one sense. This was the first time he was taken to a psychiatric unit, at the Tyrone and Fermanagh Hospital, where he stayed for 10 days.

Fanning had suffered from periods of depression ever since his mother’s death from cancer when he was 20, but things got much worse when he was 28 and living in Dublin. It was the summer of 1997 and he’d quit a full-time job to write stories and film scripts. What with the wild swings in his moods and energy levels, though, he found it increasingly difficult to get along with his father, with whom he was living. He also got kicked out of an artists’ residency, and on the way home his car ran out of petrol – such that when he called the police for help, it was for a breakdown in more than one sense. This was the first time he was taken to a psychiatric unit, at the Tyrone and Fermanagh Hospital, where he stayed for 10 days.

In the years to come there would be many more hospital stays, delusions, medication regimes and odd behavior. There would also be time spent in America – an artists’ residency in Virginia, where he met Jennifer, and a fairly long-term relationship with her in New York City – and ups and downs in his writing career. For instance, he remembers that after reading Ulysses he was so despairingly convinced that he would never be a “real writer” like James Joyce that he burned hundreds of pages of work-in-progress.

This was a very hard book for me to rate. The prologue is a brilliant 6.5-page run-on sentence in the second person and present tense (I’ve quoted a fragment above) that puts you right into the author’s experience. It is a superb piece of writing. But nothing that comes after (a more standard first-person narrative, though still in the present tense for most of it) is nearly as good. As I’ve found in some other mental health memoirs, the cycle of hospitalizations and medications gets repetitive. It’s a whole lot of telling: this happened, then that happened. That’s also true of the flashbacks to his childhood and university years.

Due to his unreliable memory of his years lost to bipolar, Fanning has had to recreate his experiences from medical records, interviews with people who knew him, and so on. This insistence on documentary realism distances the reader from what should be intimate, terrifying events. I almost wondered if this would have worked better as a novel, allowing the author to invent more and thus better capture what it actually felt like to flirt with madness. There’s no denying the extremity of this period of his life, but I found myself unable to fully engage with the retelling. (Also, this is doomed to be mistaken for the superior Brain on Fire.)

My rating:

A favorite passage:

St John of God’s carries associations for me. I attended primary school not far from here, and used to see denizens of the hospital on their day outings, conspicuous in the way they walked: hunched over, balled up, constricted, eyes down to the ground, visibly disturbed. We cruelly referred to these people as ‘mentallers’, though never to their faces or within earshot, as we were frightened of them.

Now I, too, am a mentaller.

My gut feeling: There are several stronger memoirs on the longlist, so I don’t see this one making it through.

Longlist strategy:

- I’m about halfway through both The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh.

- I finally got hold of a library copy of Murmur by Will Eaves.

- The only two books I haven’t read and don’t have access to are Astroturf and Polio. I’ll only read these if they are on the shortlist. (Fingers crossed Astroturf doesn’t make it: it sounds awful!)

The Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, March 19th, and the winner will be revealed on Wednesday, May 1st.

We plan to choose our own shortlist to announce on Friday, March 15th. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews and predictions.

Wellcome Book Prize Longlist: Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi

“This is all, ultimately, a litany of madness—the colors of it, the sounds it makes in heavy nights, the chirping of it across the shoulder of the morning.”

Magic realism and mental illness fuel a swirl of disorienting but lyrical prose in this debut novel by a Nigerian–Tamil writer. Much of the story is told by the ọgbanje (an Igbo term for evil spirits) inhabiting Ada’s head: initially we have the first person plural voice of “Smoke” and “Shadow,” who deem “the Ada” a daughter of the python goddess Ala and narrate her growing-up years in Nigeria; later we get a first-person account from Asụghara, who calls herself “a child of trauma” and leads Ada into promiscuity and drinking when she is attending college in Virginia.

Magic realism and mental illness fuel a swirl of disorienting but lyrical prose in this debut novel by a Nigerian–Tamil writer. Much of the story is told by the ọgbanje (an Igbo term for evil spirits) inhabiting Ada’s head: initially we have the first person plural voice of “Smoke” and “Shadow,” who deem “the Ada” a daughter of the python goddess Ala and narrate her growing-up years in Nigeria; later we get a first-person account from Asụghara, who calls herself “a child of trauma” and leads Ada into promiscuity and drinking when she is attending college in Virginia.

The unusual choice of narrators links Freshwater to other notable works of Nigerian literature: a spirit child relates Ben Okri’s Booker Prize-winning 1991 novel, The Famished Road, while Chigozie Obioma’s brand-new novel, An Orchestra of Minorities, is from the perspective of the main character’s chi, or life force. Emezi also contrasts indigenous belief with Christianity through Ada’s troubled relationship with “Yshwa” or “the christ.”

These spirits are parasitic and have their own agenda, yet express fondness for their hostess. “The Ada should have been nothing more than a pawn, a construct of bone and blood and muscle … But we had a loyalty to her, our little container.” So it’s with genuine pity that they document Ada’s many troubles, starting with her mother’s departure for a mental hospital and then for a job in Saudi Arabia, and continuing on through Ada’s cutting, anorexia and sexual abuse by a boyfriend. Late on in the book, Emezi also introduces gender dysphoria that causes Ada to get breast reduction surgery; to me, this felt like one complication too many.

The U.S. cover

From what I can glean from the Acknowledgments, it seems Ada’s life story might mirror Emezi’s own – at the very least, a feeling of being occupied by multiple personalities. It’s a striking book with vivid scenes and imagery, but I wanted more of Ada’s own voice, which only appears in a few brief sections totalling about six pages. The conflation of the abstract and the concrete didn’t quite work for me, and the whole is pretty melodramatic. Although I didn’t enjoy this as much as some other inside-madness tales I’ve read (such as Die, My Love and Everything Here Is Beautiful), I can admire the attempt to convey the reality of mental illness in a creative way.

My rating:

My gut feeling: I’ve only gotten to two of the five novels longlisted for the Prize, so it’s difficult to say what from the fiction is strong enough to make it through to the shortlist. Of the two, though, I think Sight would be more likely to advance than Freshwater.

Do you think this is a novel that you’d like to read?

Longlist strategy:

- I’m about one-fifth of the way through Mind on Fire by Arnold Thomas Fanning, which I plan to review in early March.

- I’ve also been sent review copies of The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh and look forward to reading them, though I might not manage to before the shortlist announcement.

- I’ve placed a library hold on Murmur by Will Eaves; if it arrives in time, I’ll try to read it before the shortlist announcement, since it’s fairly short.

- Barring these, there are only two remaining books that I haven’t read and don’t have access to: Astroturf and Polio. I’ll only read these if they make the shortlist.

The Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, March 19th, and the winner will be revealed on Wednesday, May 1st.

We plan to choose our own shortlist to announce on Friday, March 15th. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews and predictions.

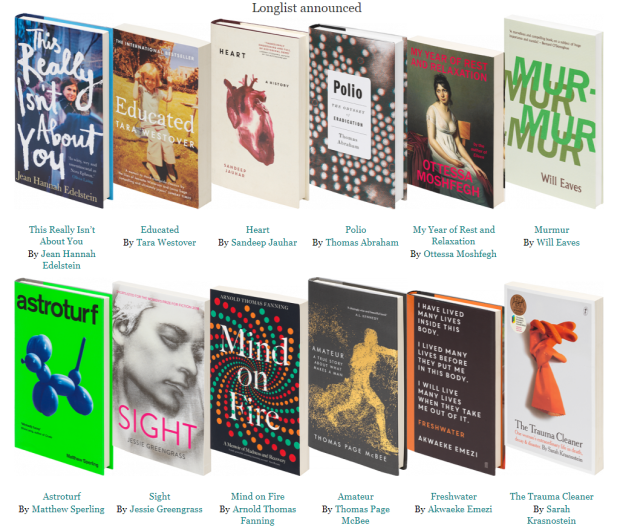

The Wellcome Book Prize 2019 Longlist: Reactions & Shadow Panel Reading Strategy

The 2019 Wellcome Book Prize longlist was announced on Tuesday. From the prize’s website, you can click on any of these 12 books’ covers, titles or authors to get more information about them.

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the prize. As always, it’s a strong and varied set of nominees, with an overall focus on gender and mental health. Here are some initial thoughts (see also Laura’s thorough rundown of the 12 nominees):

- I correctly predicted just two, Sight by Jessie Greengrass and Heart: A History by Sandeep Jauhar, but had read another three: This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein, Amateur by Thomas Page McBee, and Educated by Tara Westover (reviewed for BookBrowse).

- I’m particularly delighted to see Edelstein on the longlist as her book was one of my runners-up from last year and deserves more attention.

- I’m not personally a huge fan of the Greengrass or McBee books, but can certainly see why the judges thought them worthy of inclusion.

- Though it’s a brilliant memoir, I never would have thought to put Educated on my potential Wellcome list. However, the more I think about it, the more health elements it has: her father’s possible bipolar disorder, her brother’s brain damage, her survivalist family’s rejection of modern medicine, her mother’s career in midwifery and herbalism, and her own mental breakdown at Cambridge.

- Books I knew about and was keen to read but hadn’t thought of in conjunction with the prize: The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh.

- Novels I had heard of but wasn’t necessarily interested in beforehand: Murmur by Will Eaves and Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi. I went to get Freshwater from the library the afternoon of the longlist announcement and am now 60 pages in. I’d be tempted to call it this year’s Stay with Me except that the magic realist elements are much stronger here, reminding me of what I know about work by Chigozie Obioma and Ben Okri. The novel is narrated in the first person plural by a pair of (gods? demons? spirits?) inhabiting Ada’s head.

- And lastly, there are a few books I had never even heard of: Polio: The Odyssey of Eradication by Thomas Abraham, Mind on Fire: A Memoir of Madness and Recovery by Arnold Thomas Fanning, and Astroturf by Matthew Sperling. I’m keen on the Fanning but not so much on the other two. Polio will likely make it to the shortlist as this year’s answer to The Vaccine Race; if it does, I’ll read it then.

Some statistics on this year’s longlist, courtesy of a press release sent by Midas PR:

- Five novels (two more than last year – I think we can see the influence of novelist Elif Shafak), five memoirs, one biography, and one further nonfiction title

- Six debut authors

- Six titles from independent publishers (Canongate, CB Editions, Faber & Faber, Oneworld, Hurst Publishers, and The Text Publishing Company)

- Most of the authors are British or American, while Fanning is Irish (Emezi is Nigerian-American, Jauhar is Indian-American, and Krasnostein is Australian-American).

Chair of judges Elif Shafak writes: “In a world that remains sadly divided into echo chambers and mental ghettoes, this prize is unique in its ability to connect various disciplines: medicine, health, literature, art and science. Reading and discussing at length all the books on our list has been fascinating from the very start. We now have a wonderful longlist, of which we are all very proud. Although it sure won’t be easy to choose the shortlist, and then, finally, the winner, I am thrilled about and truly grateful for this fascinating journey through stories, ideas, ground-breaking research and revolutionary knowledge.”

We of the shadow panel have divided up the longlist titles between us as follows (though we may well each get hold of and read more of the books, simply out of personal interest) and will post reviews on our blogs within the next five weeks.

Amateur: A true story about what makes a man by Thomas Page McBee – LAURA

Astroturf by Matthew Sperling – PAUL

Educated by Tara Westover – CLARE

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi – REBECCA

Heart: A history by Sandeep Jauhar – LAURA

Mind on Fire: A memoir of madness and recovery by Arnold Thomas Fanning – REBECCA

Murmur by Will Eaves – PAUL

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh – CLARE

Polio: The odyssey of eradication by Thomas Abraham – ANNABEL

[Sight by Jessie Greengrass – 4 of us have read this; I’ll post a composite of our thoughts]

The Trauma Cleaner: One woman’s extraordinary life in death, decay and disaster by Sarah Krasnostein – ANNABEL

This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein – LAURA

The Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, March 19th, and the winner will be revealed on Wednesday, May 1st.

We plan to choose our own shortlist to announce on Friday, March 15th. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews and predictions.

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker