Tag Archives: Klara Glowczewska

Reading with the Seasons: Summer 2021, Part I

I’m more likely to choose lighter reads and dip into genre fiction in the summer than at other times of year. The past few weeks have felt more like autumn here in southern England, but summer doesn’t officially end until September 22nd. So, if I get a chance (there’s always a vague danger to labelling something “Part I”!), before then I’ll follow up with another batch of summery reads I have on the go: Goshawk Summer, Klara and the Sun, Among the Summer Snows, A Shower of Summer Days, and a few summer-into-autumn children’s books.

For this installment I have a quaint picture book, a mystery, a travel book featured for its title, and a very English classic. I’ve chosen a representative quote from each.

Summer Story by Jill Barklem (1980)

One of a quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories in small hardbacks. It wouldn’t be summer without weddings, and here one takes place between two mice, Poppy Eyebright and Dusty Dogwood (who work in the dairy and the flour mill, respectively), on Midsummer’s Day. I loved the little details about the mice preparing their outfits and the wedding feast: “Cool summer foods were being made. There was cold watercress soup, fresh dandelion salad, honey creams, syllabubs and meringues.” We’re given cutaway views of various tree stumps, like dollhouses, and the industrious activity going on within them. Like any wedding, this one has its mishaps, but all is ultimately well, like in a classical comedy. This reminded me of the Church Mice books or Beatrix Potter’s works: very sweet, quaint and English.

One of a quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories in small hardbacks. It wouldn’t be summer without weddings, and here one takes place between two mice, Poppy Eyebright and Dusty Dogwood (who work in the dairy and the flour mill, respectively), on Midsummer’s Day. I loved the little details about the mice preparing their outfits and the wedding feast: “Cool summer foods were being made. There was cold watercress soup, fresh dandelion salad, honey creams, syllabubs and meringues.” We’re given cutaway views of various tree stumps, like dollhouses, and the industrious activity going on within them. Like any wedding, this one has its mishaps, but all is ultimately well, like in a classical comedy. This reminded me of the Church Mice books or Beatrix Potter’s works: very sweet, quaint and English.

Source: Public library

My rating:

These next two give a real sense of how heat affects people, physically and emotionally.

Heatstroke by Hazel Barkworth (2020)

“In the heat, just having a human body was a chore. Just keeping it suitable for public approval was a job”

From the first word (“Languid”) on, this novel drips with hot summer atmosphere, with its opposing connotations of discomfort and sweaty sexuality. Rachel is a teacher of adolescents as well as the mother of a 15-year-old, Mia. When Lily, a pupil who also happens to be one of Mia’s best friends, goes missing, Rachel is put in a tough spot. I mostly noted how Barkworth chose to construct the plot, especially when to reveal what. By the one-quarter point, Rachel works out what’s happened to Lily; by halfway, we know why Rachel isn’t telling the police everything.

From the first word (“Languid”) on, this novel drips with hot summer atmosphere, with its opposing connotations of discomfort and sweaty sexuality. Rachel is a teacher of adolescents as well as the mother of a 15-year-old, Mia. When Lily, a pupil who also happens to be one of Mia’s best friends, goes missing, Rachel is put in a tough spot. I mostly noted how Barkworth chose to construct the plot, especially when to reveal what. By the one-quarter point, Rachel works out what’s happened to Lily; by halfway, we know why Rachel isn’t telling the police everything.

The dynamic between Rachel and Mia as they decide whether to divulge what they know is interesting. This is not the missing person mystery it at first appears to be, and I didn’t sense enough literary quality to keep me wanting to know what would happen next. I ended up skimming the last third. It would be suitable for readers of Rosamund Lupton, but novels about teenage consent are a dime a dozen these days and this paled in comparison to My Dark Vanessa. For a better sun-drenched novel, I recommend A Crime in the Neighborhood.

Source: Public library

My rating:

The Shadow of the Sun: My African Life by Ryszard Kapuściński (1998; 2001)

[Translated from the Polish by Klara Glowczewska]

“Dawn and dusk—these are the most pleasant hours in Africa. The sun is either not yet scorching, or it is no longer so—it lets you be, lets you live.”

The Polish Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This collection of essays spans decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états. Living among Africans rather than removed in a white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I read the first half last year and then picked the book back up again to finish this year. The last piece, “In the Shade of a Tree, in Africa” especially stood out. In murderously hot conditions, shade and water are two essentials. A large mango tree serves as an epicenter of activities: schooling, conversation, resting the herds, and so on. I appreciated how Kapuściński never resorts to stereotypes or flattens differences: “Africa is a thousand situations, varied, distinct, even contradictory … everything depends on where and when.”

The Polish Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This collection of essays spans decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états. Living among Africans rather than removed in a white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I read the first half last year and then picked the book back up again to finish this year. The last piece, “In the Shade of a Tree, in Africa” especially stood out. In murderously hot conditions, shade and water are two essentials. A large mango tree serves as an epicenter of activities: schooling, conversation, resting the herds, and so on. I appreciated how Kapuściński never resorts to stereotypes or flattens differences: “Africa is a thousand situations, varied, distinct, even contradictory … everything depends on where and when.”

Along with Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts and the Jan Morris anthology A Writer’s World, this is one of the best few travel books I’ve ever read.

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

August Folly by Angela Thirkell (1936)

“The sun was benignantly hot, the newly mown grass smelt sweet, bees were humming in a stupefying way, Gunnar was purring beside him, and Richard could hardly keep awake.”

I’d been curious to try Thirkell, and this fourth Barsetshire novel seemed as good a place to start as any. Richard Tebben, not the best and brightest that Oxford has to offer, is back in his parents’ village of Worsted for the summer and dreading the boredom to come. That is, until he meets beautiful Rachel Dean and is smitten – even though she’s mother to a brood of nine, most of them here with her for the holidays. He sets out to impress her by offering their donkey, Modestine, for rides for the children, and rather accidentally saving her daughter from a raging bull. Meanwhile, Richard’s sister Margaret can’t decide if she likes being wooed, and the villagers are trying to avoid being roped into Mrs Palmer’s performance of a Greek play. The dialogue can be laughably absurd. There are also a few bizarre passages that seem to come out nowhere: when no humans are around, the cat and the donkey converse.

I’d been curious to try Thirkell, and this fourth Barsetshire novel seemed as good a place to start as any. Richard Tebben, not the best and brightest that Oxford has to offer, is back in his parents’ village of Worsted for the summer and dreading the boredom to come. That is, until he meets beautiful Rachel Dean and is smitten – even though she’s mother to a brood of nine, most of them here with her for the holidays. He sets out to impress her by offering their donkey, Modestine, for rides for the children, and rather accidentally saving her daughter from a raging bull. Meanwhile, Richard’s sister Margaret can’t decide if she likes being wooed, and the villagers are trying to avoid being roped into Mrs Palmer’s performance of a Greek play. The dialogue can be laughably absurd. There are also a few bizarre passages that seem to come out nowhere: when no humans are around, the cat and the donkey converse.

This was enjoyable enough, in the same vein as books I’ve read by Barbara Pym, Miss Read, and P.G. Wodehouse, though I don’t expect I’ll pick up more by Thirkell. (No judgment intended on anyone who enjoys these authors. I got so much flak and fansplaining when I gave Pym and Wodehouse 3 stars and dared to call them fluffy or forgettable, respectively! There are times when a lighter read is just what you want, and these would also serve as quintessential English books revealing a particular era and class.)

Source: Public library

My rating:

As a bonus, I have a book about how climate change is altering familiar signs of the seasons.

Forecast: A Diary of the Lost Seasons by Joe Shute (2021)

“So many records are these days being broken that perhaps it is time to rewrite the record books, and accept the aberration has become the norm.”

Shute writes a weather column for the Telegraph, and in recent years has reported on alarming fires and flooding. He probes how the seasons are bound up with memories, conceding the danger of giving in to nostalgia for a gloried past that may never have existed. However, he provides hard evidence in the form of long-term observations (phenology) such as temperature data and photo archives that reveal that natural events like leaf fall and bud break are now occurring weeks later/earlier than they used to. He also meets farmers, hunts for cuckoos and wildflowers, and recalls journalistic assignments.

Shute writes a weather column for the Telegraph, and in recent years has reported on alarming fires and flooding. He probes how the seasons are bound up with memories, conceding the danger of giving in to nostalgia for a gloried past that may never have existed. However, he provides hard evidence in the form of long-term observations (phenology) such as temperature data and photo archives that reveal that natural events like leaf fall and bud break are now occurring weeks later/earlier than they used to. He also meets farmers, hunts for cuckoos and wildflowers, and recalls journalistic assignments.

The book deftly recreates its many scenes and conversations, and inserts statistics naturally. It also delicately weaves in a storyline about infertility: he and his wife long for a child and have tried for years to conceive, but just as the seasons are out of kilter, there seems to be something off with their bodies such that something that comes so easily for others will not for them. A male perspective on infertility is rare – I can only remember encountering it before in Native by Patrick Laurie – and these passages are really touching. The tone is of a piece with the rest of the book: thoughtful and gently melancholy, but never hopeless (alas, I found The Eternal Season by Stephen Rutt, on a rather similar topic, depressing).

Forecast is wide-ranging and so relevant – the topics it covers kept coming up and I would say to my husband, “oh yes, that’s in Joe Shute’s book.” (For example, he writes about the Ladybird What to Look For series and then we happened on an exhibit of the artwork at Mottisfont Abbey.) I can see how some might say it crams in too much or veers too much between threads, but I thought Shute handled his material admirably.

Source: Public library

My rating:

Have you been reading anything particularly fitting for summer this year?

Summery Reads, Part II: Sun and Summer Settings

Typically for the late August bank holiday, it’s turned chilly and windy here, with a fair bit of rain around. The past two weeks have felt more like autumn, but I’ve still been seeing out the season with a few summery reads.

What makes for good summer reading? I love reading with the seasons, picking up a book set during a heat wave just as the temperature is at a peak, but of course there can also be something delicious about escaping by reading about Arctic cold. Marcie of Buried in Print wrote here that she likes her summer books to offer just the right combination of the predictable and the unexpected, and that probably explains why I’m more likely to dip into genre fiction in the summer than at any other time of year. To her criteria I would also add addictiveness and a strong sense of place so as to be transporting – especially important this year when so many of us haven’t been able to have the vacations we might have planned on.

My best two summer binge reads this year were Rodham and Americanah; my two summery classics, though more subtle, were also perfect. Mostly Dead Things by Kristen Arnett, which I’m reading for a Shiny New Books review, has also felt apt for its swampy Florida setting. More recently, I picked up a couple of books with “sun” in the title, plus two novels set entirely in the course of one summer. Two of my selections are also towards my project of reading all of the Women’s Prize winners by November so I can vote on my all-time favorite.

Here comes the sun…

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2006)

Adichie filters an epic account of Nigeria’s civil war through the experience of twin sisters, Olanna and Kainene, and those closest to them. The wealthy chief’s daughters from Lagos drift apart: Olanna goes to live with Odenigbo, a math professor; Kainene is a canny businesswoman with a white lover, Richard Churchill, who is fascinated by Igbo art and plans to write a book about his experiences in Africa. Gradually, though, he realizes that the story of Biafra is not his to tell.

Adichie filters an epic account of Nigeria’s civil war through the experience of twin sisters, Olanna and Kainene, and those closest to them. The wealthy chief’s daughters from Lagos drift apart: Olanna goes to live with Odenigbo, a math professor; Kainene is a canny businesswoman with a white lover, Richard Churchill, who is fascinated by Igbo art and plans to write a book about his experiences in Africa. Gradually, though, he realizes that the story of Biafra is not his to tell.

The novel alternates between the close third-person perspectives of Olanna, Richard and Ugwu, Odenigbo’s houseboy, and moves between the early 1960s and the late 1960s. These shifts underscore stark contrasts between village life and sophisticated cocktail parties, blithe prewar days and witnessed atrocities and starvation. Kainene runs a refugee camp, while Ugwu is conscripted into the Biafran army. Violent scenes come as if out of nowhere, as suddenly as they would have upturned real lives. A jump back in time reveals an act of betrayal by Odenigbo, and apparently simple characters like Ugwu are shown to have hidden depths.

In the endmatter of my paperback reissue, Adichie writes, “If fiction is indeed the soul of history, then I was equally committed to the fiction and the history, equally keen to be true to the spirit of the time as well as to my artistic vision of it.” Copious research must have gone into a book about events that occurred before her birth (both of her grandfathers died in the conflict), but its traces are light; this is primarily about storytelling and conveying emotional realities rather than ensuring readers grasp every detail of the Biafran War. This was my second attempt to read the novel, and while again I did not find it immediately engaging, by one-quarter through it had me gripped. I’m a firm Adichie fan now, and look forward to reading her other three new-to-me books sooner rather than later.

Orange Prize (now Women’s Prize) for Fiction winner, 2007

Source: Birthday gift from my wish list some years back

My rating:

The Shadow of the Sun: My African Life by Ryszard Kapuściński (1998)

[Translated from the Polish by Klara Glowczewska in 2001]

Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This book of essays spans several decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états – including Nigeria, a nice tie-in to the Adichie. Living among the people rather than removed in some white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I’m only halfway through, but I fully expect this to stand out as one of the best travel books I’ve ever read.

Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This book of essays spans several decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états – including Nigeria, a nice tie-in to the Adichie. Living among the people rather than removed in some white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I’m only halfway through, but I fully expect this to stand out as one of the best travel books I’ve ever read.

Evocative opening lines:

“More than anything, one is struck by the light. Light everywhere. Brightness everywhere. Everywhere, the sun.”

Source: Free bookshop

It happened one summer…

A Crime in the Neighborhood by Suzanne Berne (1997)

Berne, something of a one-hit wonder, is not among the more respected Women’s Prize alumni – look at the writers she was up against in the shortlist and you have to marvel that she was considered worthier than Barbara Kingsolver (The Poisonwood Bible) and Toni Morrison (Paradise). However, I enjoyed this punchy tale. Marsha remembers the summer of 1972, when her father left her mother for Aunt Ada and news came of a young boy’s sexual assault and murder in the woods behind a mall. “If you hadn’t known what had happened in our neighborhood, the street would have looked like any other suburban street in America.”

Berne, something of a one-hit wonder, is not among the more respected Women’s Prize alumni – look at the writers she was up against in the shortlist and you have to marvel that she was considered worthier than Barbara Kingsolver (The Poisonwood Bible) and Toni Morrison (Paradise). However, I enjoyed this punchy tale. Marsha remembers the summer of 1972, when her father left her mother for Aunt Ada and news came of a young boy’s sexual assault and murder in the woods behind a mall. “If you hadn’t known what had happened in our neighborhood, the street would have looked like any other suburban street in America.”

Laid up with a broken ankle from falling out of a tree, 10-year-old Marsha stays out of the way of her snide older twin siblings and keeps a close eye on the street’s comings and goings. Like Harriet the Spy or Jimmy Stewart’s convalescent character in Rear Window, she vows to note anything relevant in her Book of Evidence to pass on to the police. Early on, her suspicion lands on Mr. Green, the bachelor who lives next door. Feeling abandoned by her father and underappreciated by the rest of her family, Marsha embellishes the facts to craft a more exciting story, not knowing or caring that she could ruin another person’s life.

The novel is set in Montgomery County, Maryland, where I grew up, and the descriptions of brutally humid days fit with my memory of the endless summer days of a childhood in the Washington, D.C. area. Although I usually avoid child narrators, I’ve always admired novels that can point to the dramatic irony between what a child experiences at the time and what a person can only understand about their situation when looking back. Stylish and rewarding.

Orange Prize (now Women’s Prize) for Fiction winner, 1999

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

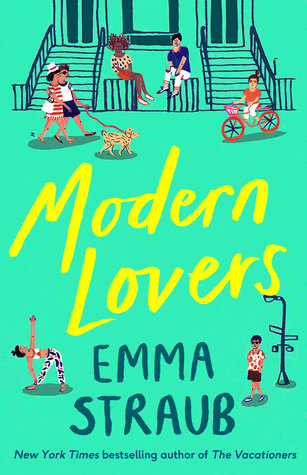

Modern Lovers by Emma Straub (2016)

Just as the Berne is a coming-of-age story masquerading as a mystery, from the title and cover this looked like it would be chick lit, but – though it has an overall breezy tone – it’s actually pretty chewy New York City literary fiction that should please fans of The Nest and/or readers of Jennifer Egan and Ann Patchett.

Just as the Berne is a coming-of-age story masquerading as a mystery, from the title and cover this looked like it would be chick lit, but – though it has an overall breezy tone – it’s actually pretty chewy New York City literary fiction that should please fans of The Nest and/or readers of Jennifer Egan and Ann Patchett.

Elizabeth Marx and Zoe Kahn-Bennett have been best friends ever since starting the student band Kitty’s Mustache at Oberlin. Now in their forties with a teenager each, they live half a block apart in Brooklyn. Zoe and her wife Jane run a neighborhood restaurant, Hyacinth; their daughter Ruby is dragging her feet about college and studying to retake the SAT over the summer. Elizabeth, a successful real estate agent, still keeps the musical flame alive; her husband Andrew, her college sweetheart from the band, is between jobs, not that his parents’ money isn’t enough to keep him afloat forever; their son, Harry, is in puppy love with Ruby.

Several things turn this one ordinary-seeming summer on its head. First, a biopic is being made about the Kitty’s Mustache singer turned solo star turned 27 Club member, Lydia, and the filmmaker needs the rest of the band on board – and especially for Elizabeth to okay their use of the hit song she wrote that launched Lydia’s brief career. Second, Andrew gets caught up in a new cult-like yoga studio run by a charismatic former actor. Third, the Kahn-Bennetts have marital and professional difficulties. Fourth, Harry and Ruby start sleeping together.

Short chapters flip between all the major characters’ perspectives, with Straub showing that she completely gets each one of them. The novel is about reassessing as one approaches adulthood or midlife, about reviving old dreams and shoring up flagging relationships. It’s nippy and funny and smart and sexy. I found so many lines that rang true:

Elizabeth was happy in her marriage, she really was. It was just that sometimes she thought about all the experiences she’d never gotten to have, and all the nights she’d listened to the sound of her husband’s snores, and wanted to jump out a window and go home with the first person who talked to her. Choices were easy to make until you realized how long life could be.

Andrew was always surprised by people’s ages now. When he was a teenager, anyone over the age of twenty looked like a grown-up, with boring clothes and a blurry face, only slightly more invisible than Charlie Brown’s teacher, but life had changed. Now everyone looked equally young, as if they could be twenty or thirty or even flirting with forty, and he couldn’t tell the difference. Maybe it was just that he was now staring in the opposite direction.

“I mean, it’s never too late to decide to do something else. Becoming an adult doesn’t mean that you suddenly have all the answers.”

I’ll definitely read more by Straub. I’d especially recommend picking this up if you enjoyed Writers & Lovers.

Source: Free bookshop

My rating: