It’s never too early to start thinking about which books might make it onto next year’s Wellcome Book Prize nominees list, open to any medical-themed books published in the UK in calendar year 2017. I’ve already read some cracking contenders, including these two memoirs from British surgeons.

Brain surgeon Henry Marsh’s first book, Do No Harm, was one of my favorite reads of 2015. In short, enthrallingly detailed chapters named after conditions he had treated or observed, he reflected on life as a surgeon, expressing sorrow over botched operations and marveling at the God-like power he wields over people’s quality of life. That first memoir saw him approaching retirement age and nearing the end of his tether with NHS bureaucracy.

Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery serves as a sort of sequel, recording Marsh’s last few weeks at his London hospital and the projects that have driven him during his first years of retirement: woodworking, renovating a derelict lock-keeper’s cottage by the canal in Oxford, and yet more neurosurgery on medical missions to Nepal and the Ukraine. But he also ranges widely over his past, recalling cases from his early years in medicine as well as from recent memory, and describing his schooling and his parents. If I were being unkind, I might say that this feels like a collection of leftover incidents from the previous book project.

However, the life of a brain surgeon is so undeniably exciting that, even if these stories are the scraps, they are delicious ones. The title has a double meaning, of course, referring not only to the patients who are admitted to the hospital but also to a surgeon’s confessions. And there are certainly many cases Marsh regrets, including operating on the wrong side in a trapped nerve patient, failing to spot that a patient was on the verge of a diabetic coma before surgery, and a young woman going blind after an operation in the Ukraine. Often there is no clear right decision, though; operating or not operating could lead to equal damage.

Once again I was struck by Marsh’s trenchant humor: he recognizes the absurdities as well as the injustices of life. In Houston he taught on a neurosurgery workshop in which students created and then treated aneurysms in live pigs. When asked “Professor, can you give us some surgical pearls?” he “thought a little apologetically of the swine in the nearby bay undergoing surgery.” A year or so later, discussing the case of a twenty-two-year-old with a fractured spine, he bitterly says, “Christopher Reeve was a millionaire and lived in America and he eventually died from complications, so what chance a poor peasant in Nepal?”

Although some slightly odd structural decisions have gone into this book – the narrative keeps jumping back to Nepal and the Ukraine, and a late chapter called “Memory” is particularly scattered in focus – I still thoroughly enjoyed reading more of Marsh’s anecdotes. The final chapter is suitably melancholy, with its sense of winding down capturing not just the somewhat slower pace of his retired life but also his awareness of the inevitable approach of death. Recalling two particularly hideous deaths he observed in his first years as a doctor, he lends theoretical approval for euthanasia as a way of maintaining dignity until the end.

What I most admire about Marsh’s writing is how he blends realism and wonder. “When my brain dies, ‘I’ will die. ‘I’ am a transient electrochemical dance, made of myriad bits of information,” he recognizes. But that doesn’t deter him from producing lyrical passages like this one: “The white corpus callosum came into view at the floor of the chasm, like a white beach between two cliffs. Running along it, like two rivers, were the anterior cerebral arteries, one on other side, bright red, pulsing gently with the heartbeat.” I highly recommend his work to readers of Atul Gawande and Paul Kalanithi.

My rating:

Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery was published in the UK by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on May 4th. My thanks to the publisher for sending a free copy for review. It will be published in the USA by Thomas Dunne Books on October 3rd.

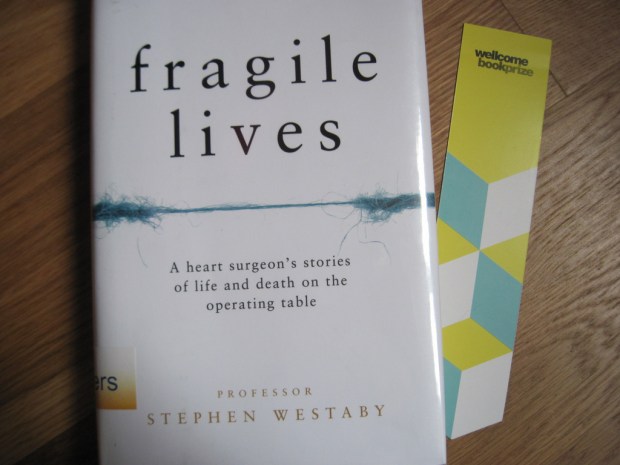

What Marsh does for brain surgery in his pair of memoirs, Professor Stephen Westaby does for heart surgery in Fragile Lives, a vivid, compassionate set of stories culled from his long career. A working class lad from Scunthorpe who watched his grandfather die of heart failure, he made his way up from hospital porter to world-leading surgeon after training at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School.

Each of these case studies, from a young African mother and her sick child whom he met while working in Saudi Arabia in the 1980s to a university student who collapses not far from his hospital in Oxford, is told in impressive depth. Although the surgery details are not for the squeamish, I found them riveting. Westaby conveys a keen sense of the adrenaline rush a surgeon gets while operating with the Grim Reaper looking on. I am not a little envious of all that he has achieved: not just saving the occasional life despite his high-mortality field – as if that weren’t enough – but also pioneering various artificial heart solutions and a tracheal bypass tube that’s named after him.

Like Marsh, he tries not to get emotionally attached to his patients, but often fails in this respect. “Surgeons are meant to be objective, not human,” he shrugs. But, also like Marsh, at his retirement he feels that NHS bureaucracy has tied his hands, denying necessary funds and equipment. Both authors come across as mavericks who don’t play by the rules, but save lives anyway. This is a fascinating read for anyone who enjoys books on a medical theme.

A few favorite lines:

“We stop life and start it again, making things better, taking calculated risks.”

“We were adrenaline junkies living on a continuous high, craving action. From bleeding patients to cardiac arrests. From theatre to intensive care. From pub to party.”

My rating:

Fragile Lives: A Heart Surgeon’s Stories of Life and Death on the Operating Table was published in the UK by HarperCollins on February 9th. I read a public library copy. It will be published in the USA, by Basic Books, under the title Open Heart on June 20th.

I read an article in which Marsh talked about that case of the woman with diabetes – so moving to hear him talk about the failures that led to her death.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was indeed a moving scene in the book. Really it was the result of a collection of little mistakes and omissions made by various staff members, but he was humble enough to be the one to make the apology to the family.

LikeLike

He struck me as a man with a huge amount of integrity

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read Fragile Lives, but I liked Admissions very much—I could sense that Marsh was an angry and occasionally volatile person, and some of his descriptions of his own reactions made me think I’d have a hard time working with him, but he is so forthcoming about his flaws and failures that he largely disarms any negative feelings a reader might have towards him. And he discusses end-of-life care with such honesty, as well.

LikeLike

Oh, he definitely comes across as someone with a temper! I imagine there were many at his hospital who were not sad to see him go. Did you also read Do No Harm? It’s the better book, I think.

LikeLike

No, not yet – but interesting that you think it’s better. I know it was received rapturously when it came out!

LikeLike

This one struck me as quite unstructured, whereas in his first book he uses medical conditions as chapter titles to focus the material.

LikeLike

A doctor woke me up in the middle of an abdominal operation. So why isn’t there an international crimes court for surgeons? (From what I gather, Marsh would be hung.)

LikeLike

Yikes! He certainly made his share of mistakes, but at least he’s honest about them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s something weird abour surgeons. (A Kevorkian twist, although Dr. Death was a pathologist.) Some of the best ones are bonkers in my estimate — yet they have saved my life several times. Grazie mille!

LikeLike

I loved Do No Harm, I will absolutely look out for Fragile Lives. When I worked in that world I avoided all TV medical dramas and books, but now I’ve been out of nursing for a while I have a new appreciation, especially for such well-written and deeply considered work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved Do No Harm and Fragile Lives, although I preferred Marsh’s style. Looking forward to this one too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those were both 5-star reads for me. I’d agree that Marsh has the more literary style.

LikeLike

Not books I can read but I appreciate your balanced and detailed reviews, as ever. I find surgeons seem to come in two versions, arrogant and humble. Having met one of each recently, I’m glad I had the choice / made the right choice (esp as a friend saw my surgeon this week and I was able to reassure her that she would keep her and her choices as priority as far as she could).

LikeLike

I think Marsh was probably an odd combination of the two traits: confident in his skill and very impatient of others’ shortcomings, yet also willing to admit mistakes. He certainly had a short temper: he recounts tweaking a nurse’s nose in his last few weeks at the hospital when he wasn’t being obeyed quickly enough!

I met my mother’s knee surgeon a couple summers ago and he was certainly an odd duck. He looked like John Malkovich, was brusque yet jokey, and did voice transcription of his records via his computer to someone in India (which I really didn’t think could be efficient).

LikeLike

These sound fascinating! I would imagine you’d have to be a special kind of a person to become a surgeon. I know I could never handle all the pressure and the need to make quick decisions about someone’s life. I often wonder how many mistakes are made – it’s good to hear they talk about the bad along with the good. How awful to have to live with the mistakes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A livelihood (calling?) that I can not imagine pursuing. The bits of Marsh’s writing that you shared were lovely, though.

LikeLike

No, I can’t imagine being directly responsible for other people’s life or death either!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Fragile Lives by Stephen Westaby: This is a vivid, compassionate set of stories culled from the author’s long career in heart surgery. Westaby conveys a keen sense of the adrenaline rush a surgeon gets while operating with the Grim Reaper looking on. I am not a little envious of all that he has achieved: not just saving the occasional life despite his high-mortality field – as if that weren’t enough – but also pioneering various artificial heart solutions and a tracheal bypass tube that’s named after him. […]

LikeLike

[…] Fragile Lives by Stephen Westaby: This is a vivid, compassionate set of stories culled from the author’s long career in heart surgery with the Grim Reaper looking on. I am not a little envious of all that Westaby has achieved: not just saving the occasional life despite his high-mortality field – as if that weren’t enough – but also pioneering various artificial heart solutions and a tracheal bypass tube that’s named after him. […]

LikeLike

[…] Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh […]

LikeLike

[…] recommend this memoir to readers of Kathryn Mannix’s With the End in Mind and Henry Marsh’s Admissions. But with its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone […]

LikeLike

[…] Henry Marsh in Admissions, she expresses regret for moments when she was in a rush or trying to impress seniors and didn’t […]

LikeLike

[…] surgeon and the author of Do No Harm, one of the very best medical memoirs out there, as well as Admissions. As he was turning 70 a couple of years ago, two specific happenings prompted this third book. One: […]

LikeLike